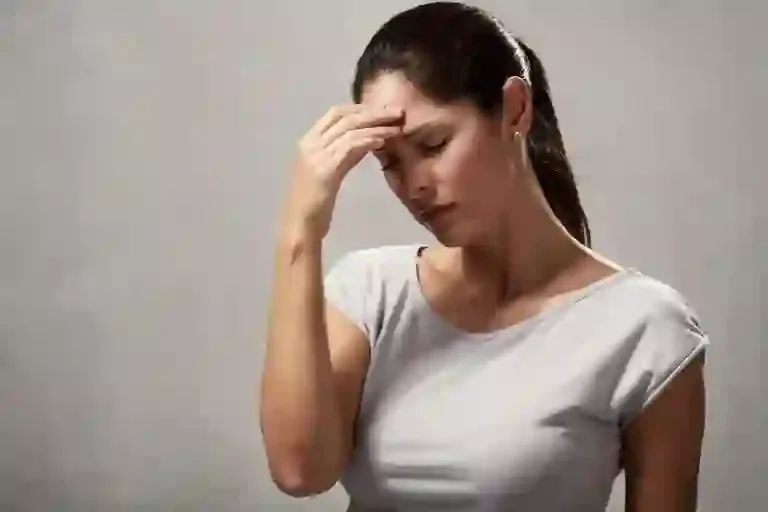

When all’s not well, surgeons often rely on voices in their head, where ideas and uplifting thoughts are sometimes replaced with self-questioning

Wake up, Elizabeth, your operation is over; everything went off very well. Now, open your eyes,” I heard the anesthetist bellow as they went through the routine of reversing the anesthesia to awaken the patient and remove the breathing tube.

It was an operation to clip an unruptured aneurysm arising from the bifurcation of the right internal carotid artery. I sat in one corner of the operating room writing down the post-op orders, feeling a kind of inner joy as I typed out my notes for having performed a masterful surgery. After I finished, I made a quick dash with my team to check on our admitted patients. When I returned to the ICU an hour later, I was informed that Elizabeth hadn’t been shifted yet.

“That’s strange,” I said to myself, swiftly climbing the stairs that led to the operating room to hear four words from the anesthetist that no surgeon wants to ever hear: “She’s not waking up.”

The anesthetist peered right into my eyes. “The muscle relaxant has been reversed, blood gas analysis is fine, but she’s just not opening her eyes,” she finished, looked at me with the finality of not having a plausible explanation for this from her end. This was also her polite way of saying, you’ve done something wrong inside, now fix it.

I went through the steps of surgery in my mind, running my hands through my scanty hair. Could it be because we buzzed a surface vein? Have I taken a perforating artery supplying the hypothalamus in the clip? Did we retract the brain too much? Is the main artery kinked by the clip?

The self-introspection then made way for chatter. Should I have operated on her in the first place? I should have just asked the interventional radiologist to coil the aneurysm. She’s a mother of two, have I destroyed her family? Do I really think I have the skill to do these complex cases? Who am I trying to impress? And at whose expense? Better do something before it’s too late. Or, is the damage already done? It’s a sickening feeling when someone you’ve operated on doesn’t wake up the way you expect them to. It is literally gut-wrenching; your intestines feel as though they are physically being squeezed.

I looked at the numbers on the monitor and then at the anesthetist repeating the same words, over and over: “Wake up, Elizabeth, wake up—your surgery is over.”

“Raise the blood pressure to 170-180,” I ordered, thinking that some crucial vessel might be in spasm. She transiently opened her eyes, but within a few seconds went back into a deep slumber. We got an urgent MRI done, but that was clean; no area of ischemia or infarction. No blood clots as well. The clip was positioned perfectly, and we ruled out her having subclinical seizures, too. We shifted her to the ICU on the breathing tube as my gaze vacillated between the monitor and her body lying motionless when it should have been sitting up in bed and talking to me instead.

The chatter turned to a full-blown tirade. Am I missing something here? Should I call someone and ask for help? Should I just give this sometime? What would I do if someone else operated on this patient and I was called to opine on how to proceed? I use this last analogy a lot when I’m in distress. I try and distance myself from the problem at hand, and adopt the fly-on-the-wall approach. It’s easier said than done, of course, but all you have to do is zoom out. I remember reading somewhere, “The only people who see the whole picture, are the ones who step out of the frame.”

There is a Chinese proverb that says, “He who blames others has a long way to go on his journey. He who blames himself is halfway there. He who blames no one has arrived.” I was halfway there. The countless permutations and combinations of the infinite possibilities of things that could have gone wrong kept buzzing in my head.

We all have a voice in our heads. We tune into its incessant chatter to look for ideas, guidance, and wisdom.

Sometimes, these conversations uplift us and sometimes they sink us into the deep, dark hole of despair.

Ethan Kross, a renowned experimental psychologist, and neuroscientist, and one of the world’s leading experts on how to control the conscious mind, has written a book called Chatter: The Voice in Our Head, Why It Matters, and How to Harness. In that, he states, “In recent years, a robust body of new research has demonstrated that when we experience distress, engaging in introspection often does more harm than good. It undermines our performance at work, interferes with our ability to make good decisions, and negatively influences our relationships.”

Instead, he reveals the tools you need, to harness that voice, so that you can be happier, healthier, and more productive. “Chatter doesn’t simply hurt people in an emotional sense, it has physical implications for our body as well, from the way we experience physical pain all the way down, to the way our genes operate in our cell,” he warns.

I hadn’t read the book at the time, and my head was spinning with thoughts as I stood at the edge of her bed for three hours, waiting for her to move just a little. I was following the old age adage of “just give it time” when dealing with this unsettling experience.

After a long, painful wait, Elizabeth moved a little. And then, a lot. She opened her eyes and made chewing movements and brought her arms to the tube as if to denote she wanted it out. We took it out once she was fully awake and briskly obeying commands, indicating to us that she was conscious, alert, and aware.

I am still intrigued about why she took so long to wake up. Probably, it was a tiny artery that went into spasm but opened up later. But, the relief of shifting her out of the ICU the next morning and then home with the family in a few days was intense. Finally, there was no one to blame.

The writer is practicing neurosurgeon at Wockhardt Hospitals and Honorary Assistant Professor of Neurosurgery at Grant Medical College and Sir JJ Group of Hospitals.

Source: https://www.mid-day.com/news/opinion/article/their-worries-our-stories-23175713